The Causes of the Great Depression

The Great Depression was the worst economic crisis in American history. It began in 1929 and lasted through the 1930s, affecting millions of Americans. But it didn’t happen overnight. The Depression was the result of several long-term economic problems and one dramatic crash that exposed how fragile the economy really was. To understand what went wrong, we need to look at the 1920s—a decade of booming business, rising stock prices, and modern lifestyles—but also one full of hidden weaknesses.

Farming Practices and Overproduction in the 1920s

While many Americans in the 1920s celebrated prosperity, farmers were already in trouble. During World War I, farmers had increased food production to feed both American soldiers and European allies. To meet this demand, they borrowed money to buy more land, tractors, and equipment. But when the war ended, European farms recovered and no longer needed as many imports. Suddenly, American farmers had too much food and not enough buyers.

This overproduction led to falling prices. Crops like wheat, corn, and cotton flooded the market, and their value dropped sharply. Many farmers couldn’t make enough money to pay back their loans. As a result, foreclosures increased, and rural poverty spread. Even though cities and factories seemed to be booming, America’s agricultural backbone was already buckling under the weight of debt and low prices. The struggles of farmers were an early warning sign that the economy wasn’t as strong as it looked.

“Farm foreclosures pre-dated the onset of the Depression. The agricultural depression, reflecting a sharp drop in demand for farm produce, was already nearly a decade old at the time of the stock market crash in 1929. Farmers had prospered during the 1910s, particularly during the World War I years of 1914-1918, as wartime conditions in Europe and the wartime boom in the U.S. created demand for farm products. Farmers borrowed heavily to buy new land and equipment to increase production.

The sudden drop in demand resulting from the war’s end and the resulting decline in income caught many farmers by surprise. Agricultural foreclosures rates rose steadily throughout the 1920s.”

Daniel Leab (editor), The Great Depression and the New Deal (2010)

The Stock Market Crash of 1929

In the late 1920s, the stock market became a symbol of wealth and success. Millions of Americans bought stocks, often with borrowed money. This practice, called buying on margin, allowed investors to purchase stocks by paying only a small portion of the price upfront, with the rest covered by loans. As long as stock prices kept rising, this seemed like a safe bet.

It was so common that everyone in New York City was involved, and if you weren’t involved you were falling behind.

“The stock market hysteria reached its apex in 1929. Everyone gave you tips for a rise. Every was playing the market. Stocks soared dizzily. I found it hard not to be engulfed. I had invested my American earnings in good stocks. Should I sell for a profit? Everyone said, "Hang on - it's a rising market". On my last day in New York I went down to the barber. As he removed the sheet he said softly, "Buy Standard Gas. I've doubled. It's good for another double." As I walked upstairs, I reflected that if the hysteria had reached the barber-level, something must soon happen.” - Cecil Roberts, The Bright Twenties (1938)”

But the market couldn’t rise forever. By the fall of 1929, stock prices had reached unrealistic highs. On October 29, 1929, known as Black Tuesday, the market crashed. Prices fell sharply, and panic set in. Investors rushed to sell their stocks, but there were few buyers. Billions of dollars in wealth vanished almost overnight.

The crash did not cause the Great Depression by itself, but it exposed deep problems in the economy. It also caused banks to fail, businesses to lose confidence, and people to stop spending money. The crash was the match that lit an already dry pile of economic problems.

In addition to the Stock Market Crash. Bank’s also failed at a massive rate. Banks earn money by earning interest on loans to customers. When the stock market crashed, nervous investors rushed to take their savings out of the bank. However, the banks had loaned most of the money, and didn’t have the cash in their bank vaults. If the bank didn’t have enough money to run, the bank would fail and close.

Protective Tariffs and the Global Economy

Another factor that made the Depression worse was the U.S. government’s use of protective tariffs—taxes on imported goods. The idea was to protect American factories and farms by making foreign products more expensive. One of the most famous examples is the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, passed in 1930.

This backfired. Other countries responded by placing their own tariffs on American goods. Global trade slowed down dramatically. American farmers and manufacturers, already struggling, now had an even harder time selling their products overseas. The world economy became more isolated and more fragile. Instead of helping American businesses, tariffs deepened the Depression at home and abroad.

“The Fordney-McCumber Act (1922) raised tariffs to levels higher than any previously in American history in an attempt to bolster the post-war economy, protect new war industries, and aid farmers. Duties on chinaware, pig iron, textiles, sugar, and rails were restored to the high levels of 1907 and increases ranging from 60 to 400 per cent were established on dyes, chemicals, silk and rayon textiles, and hardware. Tariffs on a variety of agricultural produce were raised. Although the tariffs encouraged the growth of monopoly in the United States, they also made it difficult for European powers to earn [enough money] to repay war debts. Other nations responded by increasing their tariffs thus limiting United States exports... These factors helped to create the weaknesses that produced the Depression.”

Neil Wynn, The A to Z from the Great War to the Great Depression (2009)

The Wealth Gap and Economic Inequality

In the 1920s, the United States experienced rapid economic growth—but that wealth wasn’t shared equally. A small percentage of Americans controlled most of the country’s money, while millions of others lived paycheck to paycheck. The wealth gap between the rich and the poor grew wider each year.

Many workers did not earn enough to afford the products being mass-produced in factories. While upper-class Americans bought luxury items, the majority of the population couldn’t participate fully in the consumer economy. This imbalance meant that companies were making more goods than people could afford to buy. The economy looked strong on the surface, but it was built on shaky foundations.

“The average industrial wage rose from 1919's $1,158 to $1,304 in 1927, a solid if unspectacular gain, during a period of mainly stable prices... The twenties brought an average increase in income of about 35%. But the biggest gain went to the people earning more than $3,000 a year.... The number of millionaires had risen from 7,000 in 1914 to about 35,000 in 1928.”

Geoffrey Perrett, America in the 20's (1982)

Consumer Spending and Easy Credit

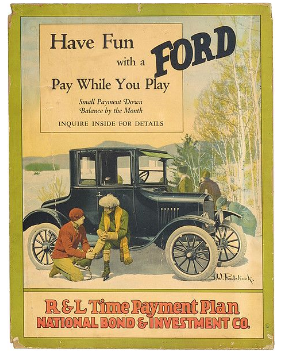

One reason the 1920s economy seemed so strong was the rise in consumer spending—Americans were buying radios, refrigerators, cars, and other new inventions. But much of this spending was done on credit. New installment plans allowed people to "buy now and pay later." At first, this helped boost the economy, but over time, it created a dangerous cycle of debt.

Here is a quote that illustrates the danger of installment buying:

”“All statistics aside, installment buying is a rapidly growing evil. It is inflation of the worst kind. Installment buyers pledge their earnings for years in advance; and then when hard times come as they inevitably will this large debtor class finds itself forced to pay in deflated, higher-value dollars, what they had contracted for when dollars were cheap. . . . Installment buying is an attempt to keep up with the Joneses, to satisfy every passing want; and it is creating a condition that is certainly unsound and, in many cases, results in weakening of character and neglect of the more substantial things of life.” - James Couzens, Former VP, Ford Motor Co.; U.S. Senator from Michigan

People paid for all sorts of different things with installment plans. “The rise and spread of the dollar-down -and-so-much-per plan extends credit for virtually everything homes, $200 over-stuffed living-room suites, electric washing machines, automobiles, fur coats, diamond rings to persons of whom frequently little is known as to their intention or ability to pay. Likewise, the building of a house by the local carpenter today is increasingly ceasing to be the simple act of tool-using in return for the prompt payment of a sum of money.” -Robert S. Lynd & Helen Merrell Lynd Middletown: A Study in American Culture (1929)"

When people ran out of money or lost confidence in the economy, they stopped spending. Suddenly, companies had warehouses full of unsold products. As sales dropped, businesses cut production and laid off workers. Unemployment rose. With fewer people earning wages, consumer spending dropped even more. The economy spiraled downward.

Conclusion: A Perfect Storm

The Great Depression didn’t have just one cause. It was the result of many interconnected problems: a struggling farming sector, a stock market bubble, unwise tariff policies, unequal wealth distribution, and too much reliance on credit and consumer debt. These issues built up over time, and when the stock market crashed in 1929, they all came crashing down together.

Understanding these causes helps us see how economic systems can look healthy while hiding deep problems—and why strong foundations matter more than flashy success.

Popular stocks and their values before and after Black Tuesday.